Kilimanjaro is most popular for climbing the great mountain and is not primarily a wildlife destination.

However, the national park supports four different vegetation zones, each with its own distinct flora and fauna.

Montane Forest Zone

The most biodiverse vegetation zone is the lush evergreen rainforest that dominates from altitudes of 1,800m (5,906ft) up to 3,000m (9,843ft).

The Montane Forest Zone is the wettest part of the mountain, with the southern slopes receiving up to 2,000mm of rain annually. It looks and feels like the archetypal tropical jungle – hot, humid, colored in infinite shades of green and alive with bird song.

More than 1,200 vascular plant species have been recorded in these forests, many endemic to this one mountain.

Common forest trees include the towering East African camphorwood Ocotea usambarensis, Yellowwood Podocarpus latifolius, and various wild figs Ficus.

There is also as well as the wild olive Olea Africana, macaranga Macaranga kilimandscharica and, at higher altitudes, fragrant Hagenia Hagenia abyssinica draped atmospherically in old-man’s beard lichens, and African pencil-cedar Juniperus procera.

Seasonal flowers include the stunning tuba-shaped red-and-yellow Impatiens kilimanjari and various violets and epiphytic orchids. Another feature of the higher forest zone is large stands of towering bamboo forest.

The most frequently seen forest mammals are monkeys. Troops of black-and-white colobus leap acrobatically between the trees, long white tails in tow, while a habituated troop of the lovely blue monkey frequents some of the overnight huts.

Buffalo and elephants are present but seldom seen, though you might well notice their fresh spoor on the forest trails.

Predators such as leopards and servals are even more elusive, but you might catch a glimpse of the beautifully marked bushbuck or one of three recorded species of duiker.

The largest of these, the elusive Abbott’s duiker, is an endangered species now regarded as endemic to a quintet of montane forests in eastern Tanzania due to environmental loss and poaching elsewhere in its natural range.

After dark, the night air is frequently shattered by the banshee wail of the otherwise unobtrusive tree hyrax.

The forest birdlife is sensational, perfect for a birding safari. You’re almost certain to see a silvery-cheeked hornbill, a massive and rather comical bird that reveals its presence with a raucous nasal call and heavy wingbeats.

There’s also the stellar Hartlaub’s turaco, a green and purple bird with deep red underwings, the noisy but elusive emerald cuckoo, and a host of colourful robin-chats, drab but cheerful greenbuls, and nectar-loving sunbirds.

Other wildlife includes plentiful butterflies (including at least four endemic species), the hulking foot-long Jackson’s three-horned chameleon, the slightly smaller Kilimanjaro two-horned chameleon, and numerous small but colourful tree frogs.

Semi-Alpine Moorland Zone

The dominant vegetation zone between the 3,000m (9,843ft) and 4,000m (13,123ft) contours is a heath-like cover studded with abundant wildflowers.

It’s resident species include the exquisite yellow-flowered alpine sugarbush Protea kilimandscharica and alpine red-hot poker Kniphofia thomsonii.

Though less biodiverse than the forest zone, the pastel-shaded moorland has an ethereal beauty, particularly in the morning when it’s often shrouded in mist.

This zone is notable for the presence of two most distinctive plants: the giant lobelia Lobelia deckenii and the giant groundsel Dendrosenecio kilimanjari.

The giant lobelia Lobelia deckenii grows to 3m (10ft) high and is capped by a massive whorled rosette, and the giant groundsel Dendrosenecio kilimanjari, grows up to 5m (16ft) high and is capped by a spike of yellow flowers.

Aside from small rodents such as the ubiquitous four-striped grass mouse, mammal densities are low in the moorland zone. But look out for the endearing rock hyrax and pairs of klipspringer that sometimes stand sentinel on rocky outcrops.

![]()

Birdlife is limited to a few species adapted to high-altitude environments. The star among these is the scarlet-tufted malachite sunbird, a beautiful iridescent green bird often seen feeding on proteas and red-hot pokers.

It’s run a close second by the spectacular but scarce lammergeyer (bearded vulture).

Other birds of the moorland zone include Augur buzzard, Mountain buzzard, Alpine swift, Alpine chat, and Streaky seedeater.

Alpine Zone

Classified as a semi-desert because of its low rainfall, the alpine zone – roughly between 4,000m (13,123ft) and 5,000m (16,404ft) – also experiences dramatic daily temperature contrasts.

Plant life is restricted to around 55 hardy species of grass, lichen, and moss. The common eland – Africa’s largest antelope – occasionally strays up into this zone, and elephants have been recorded upon occasion, but essentially there is no wildlife at these heights.

Arctic Zone

Above the 5,000m (16,404ft) contour, rainfall is practically non-existent, and permanent life forms are restricted to a few masochistic lichens.

As for large wildlife, a pack of African wild dogs was observed here in 1962, and a frozen leopard was discovered in 1926.

Outside the Park

It’s worth noting that the Tanzania/Kenya border region occupied by Kilimanjaro supports some of the world’s finest ‘Big Five’ reserves. These include the world-famous Serengeti National Park and the abutting Masai Mara National Reserve.

Furthermore, two superb game-viewing destinations lie in the shadow of the great mountain itself.

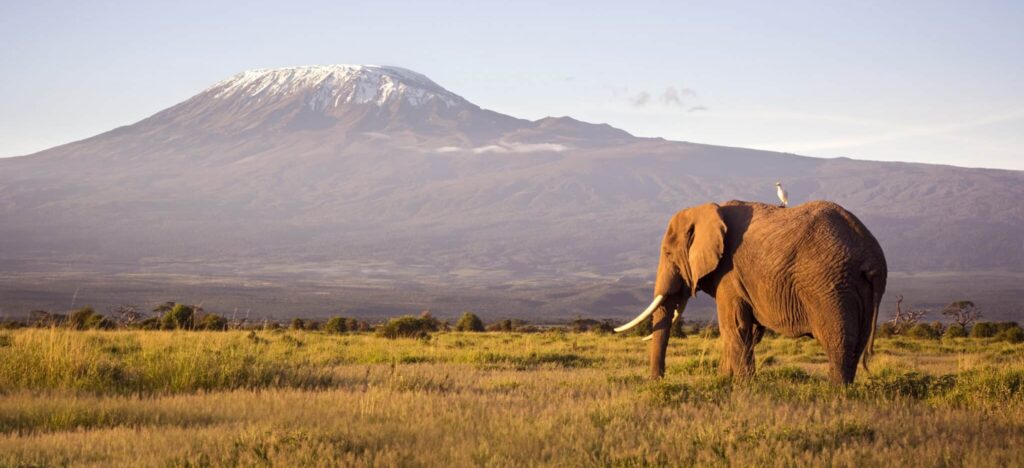

Kenya’s famous Amboseli National Park is where most iconic photographs of elephants crossing the dusty plain, or giraffes nibbling on an acacia below the snow-capped peak of Kilimanjaro, were captured.

Rather more obscure is Tanzania’s West Kilimanjaro, a wedge of dry savanna protected as a wildlife management area in collaboration with local Masai pastoralists.

It’s notable not only for offering superb in-your-face views of Kilimanjaro but also for its plentiful wildlife, which includes elephants, lions, cheetahs, and typical dry-country antelope.