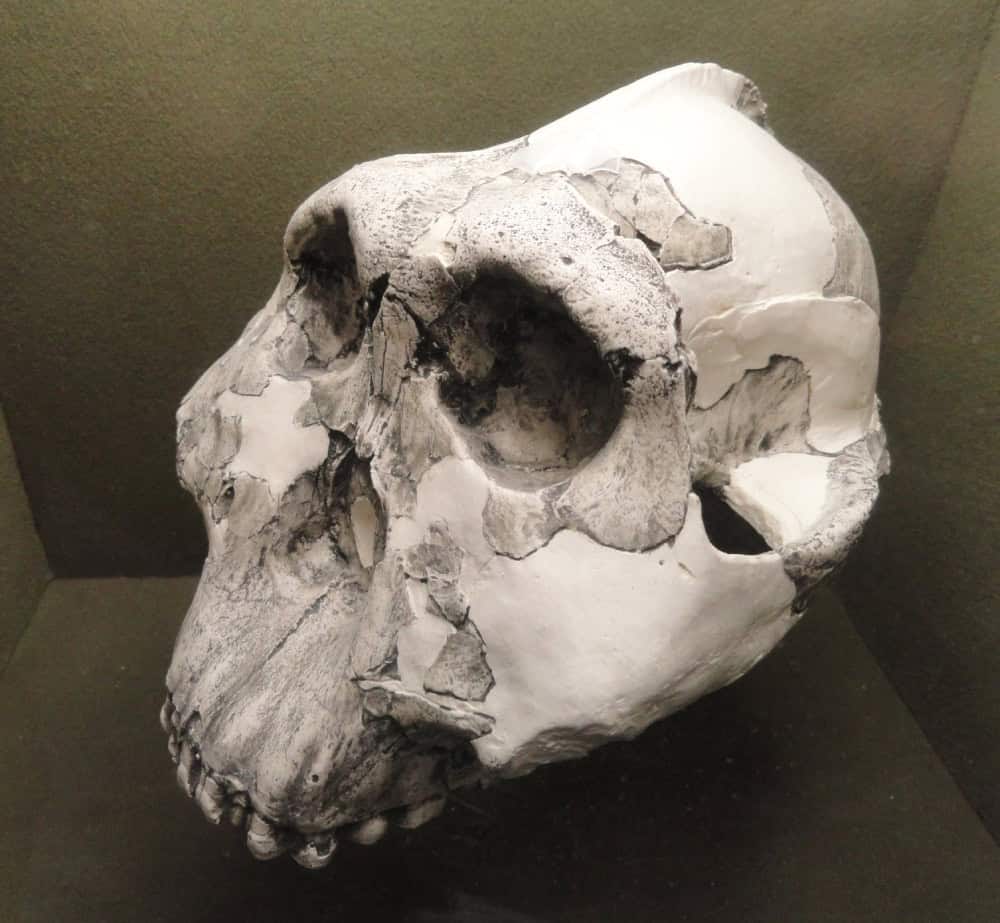

Two million years ago, the landscape of Ngorongoro Conservation Area looked very different to how it does today. Ngorongoro itself would have been an active volcano, taller perhaps than Kilimanjaro is now, and the seasonally parched plains at its western base were partially submerged beneath a seasonal lake that formed an important watering hole for our hominid ancestors. The fluctuating nature of this ancient lake led to a high level of stratification, one that accentuated by sporadic deposits of volcanic ash from Crater Highlands, creating ideal conditions for the fossilisation. Then, tens of thousands of years ago, fresh tectonic activity caused the land to tilt, leading to the formation of a new lake to the east and the creation of a seasonal river that cut through the former lakebed to expose layers of stratification up to 100m deep and a continuous archaeological and fossil record of life on the plains over the past two million years. Named after the Maasai word for the wild sisal that grows in the area, Oldupai Gorge is one of the richest palaeontological sites in East Africa. First excavated in 1931 by Professor Louis Leakey, it was here, in 1959, that Louis’s wife Mary Leakey unearthed a critical landmark in the history of palaeontology: the discovery of a fossilised cranium that provided the first conclusive evidence that hominid evolution stretched back over more than a million years and had been enacted on the plains of East Africa. Nicknamed ‘Nutcracker Man’ in reference to its bulky jawbone, the cranium belonged to a robust Australopithecine that had lived and died on the ancient lakeshore around 1.75 million years earlier, and while its antiquity would later be superseded by more ancient fossils unearthed in Ethiopia and Kenya, it rewrote the perceived timespan of human evolution, shot the Leakeys’ work to international prominence, and led to an a series of exciting new discoveries, including the first fossilised remains of Homo habilis. At nearby Laetoli, in 1976, four years after Louis’s death, Mary Leakey discovered footprints created more than three million years ago by a party of early hominids that had walked through a bed of freshly deposited volcanic ash – still the most ancient hominid footprints ever found.

Today, the original diggings can be explored with a guide, but the main attraction is an excellent site museum that lies a short distance off the main track connecting Ngorongoro Crater to Serengeti National Park. Displays include replicas of some of the more interesting hominid fossils unearthed at the site as well as the Laetoli footprints, along with genuine fossils of a menagerie of extinct oddities: a short-necked giraffe, a giant swine, an aquatic elephant and a bizarre antelope with long de-curved horns. Outside the museum, look out for colourful dry-country birds such as red-and-yellow barbet and purple grenadier.